What happens when the healer needs healing?

“Physician, heal thyself!” is the ancient proverb quoted in St. Luke’s Gospel. But for Brian Greenwood, a chaplain at the Grey Nuns Community Hospital in Edmonton since 2009, it might take on a different spin. In his case, it might be “Chaplain, heal your spirit.”

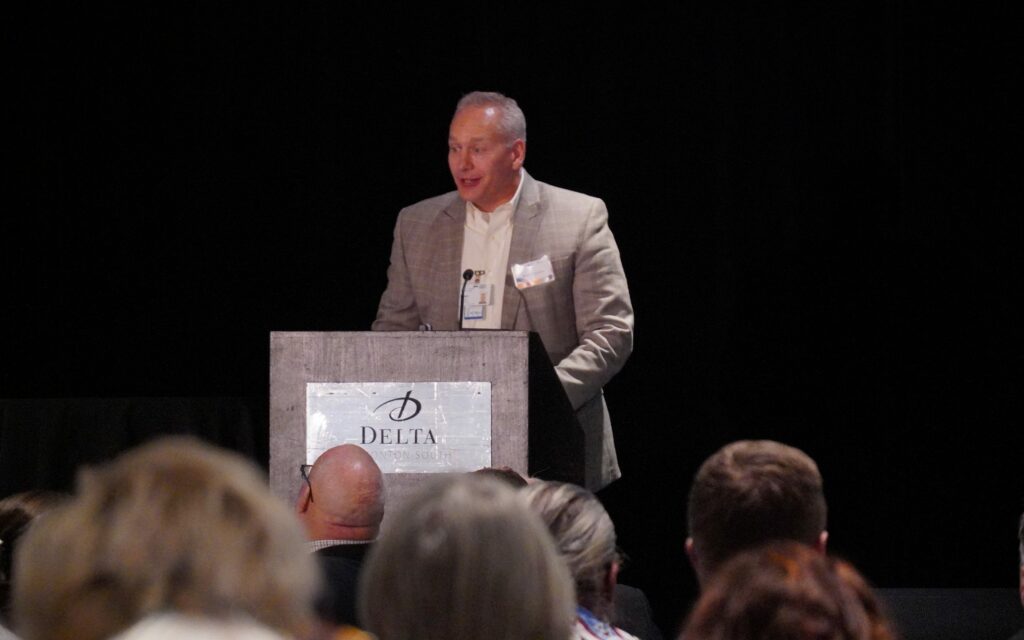

Greenwood first shared his harrowing journey of depression, to the point of suicidal thoughts, and recovery three years ago with the readership of the Covenant Health news site, The Vital Beat. Hundreds now know his story after the Catholic health care provider’s Annual Community Meeting on Oct. 23 featured him as a keynote speaker.

The meeting also signalled release of Covenant Health’s annual report at a challenging time.

“This has been a year of great success in terms of our ability to reach out to communities and delve our services and to expand and innovate and grow,” said Patrick Dumelie, chief executive officer.

“Challenges ahead, we are obviously in a time – signalled by government and the Blue Ribbon Panel (on Alberta’s finances) – that we’re in a belt-tightening phase. So for us, it’s to make sure we stick to our values and look to find innovative ways to look after our patients and residents and clients.”

Health care is Alberta’s largest expense, making up an estimated 40 per cent of total operating costs. In the provincial budget released last week, $40 million was allocated to respond to the opioid crisis and $100 million for a mental health and addiction strategy.

Greenwood’s story details his search for his own personal mental health strategy.

“I’m doing 100 per cent,” he said in an interview after his speech. “Full recovery from my type of illness is possible if you take certain steps. If you involve certain steps, it’s even probable. There is hope. And recovery is possible.”

One in five people in Canada will personally experience a mental health problem or illness, with anxiety and depression being the most common, according to statistics cited by Covenant Health. Yet almost half – 49 per cent – have never gone to see a doctor.

Mental health also takes an economic toll. The cost of in Canada was estimated in 1998 to be at least $7.9 billion – $4.7 billion in care and $3.2 billion in disability and early death. And it’s why Covenant Health has made it a top priority.

“For us, our board has been really clear, that people with mental illness and addictions require our help. Oftentimes our health system, I believe, doesn’t do an adequate job in supporting individuals. It’s so prevalent in our society and yet it goes untreated,” Dumelie said.

“When I think about Brian, I think about all of the assets that he had and he still had this mental illness,” Dumelie added. “This is a very strong person, has all sorts of skills as a chaplain, has his prayer life, has his family, and yet he had such extreme difficulties from this mental illness.

“It really speaks to me about how mental illness can affect all of us.”

For 10 years, the Greenwood family was in “constant crisis” around one son. “We watched as our beloved spiralled into unresponsive drug addiction, then alcohol abuse, then criminal charges.”

They had been to “innumerable” counsellors, rehabilitation programs, court hearings, psychiatric interventions. At one point they had police at their home five times over four nights. They pleaded with judges for treatment orders.

“We looked on powerless as our beloved damaged neighbours’ property looking for cameras that were watching,” Greenwood recalled.

The situation had deteriorated to a point where Greenwood himself considered suicide.

“As a father, I did what any father would do. After 10 years of this I said, ‘I want to absorb that pain. I want to satisfy it. I want to appease (the son’s) spiritual pain.’ I thought if I suicided, it would spare them this painful path. I believed the delusion that I could take the suicide bullet for them.

“It was developed as an attempt to take the bullet for a beloved person in my life who was struggling.

“It’s not weak people who commit suicide,” Greenwood added. “I was a rugby player. I’ve packed down, scrummed down, rugby-ed down, mauled with some of the best athletes in the world.”

What followed was the start of his recovery. Greenwood checked himself into his own hospital, the Grey Nuns, in November 2015 and found a supportive community. He said he suffered from “internal embarrassment” at his situation, not from anyone else. Greenwood didn’t leave his room for three weeks except for meals and electro-convulsive therapy. “And I got better.”

With cognitive behavioural therapy, psychotherapy and medication, Greenwood’s condition improved enough that he could return to work and the “challenge of changing my son. And I did … For almost a year.

“I read some books on mind over matter and decided I didn’t need meds. I learned that if you don’t mind, it doesn’t matter,” Greenwood joked. “Going off psych meds, cold turkey, without your doctor’s knowledge will not only get you a whipping from him, but it’s not like coasting to a landing as if you’re in a two-engine plane without one engine. It’s like dropping out of the sky in a gunshot helicopter, spinning and falling without control.”

Greenwood managed to get back on track with a regimen that applies to many who are recovering from mental illness. He became religious about taking his medication – “Eighteen rounds of electro-convulsive therapy helped bump me off the train track too.” He rediscovered his passion for friendships, rugby and flyfishing. And he guarded against isolating himself from friends and family.

“I will get better,” he promised himself. “I forced myself out. I resisted the temptation to let calls from friends go to voicemail. We have a saying as chaplains: ‘Not everyone has a religion, but everyone has a spirit.’ And spirituality is anything that gives you meaning and purpose. Connect with something bigger than yourself that fills you with a sense of awe and connectiveness to your environment.”

Prayer helped too. Greenwood created his own 21-bead prayer bracelet that he now wears all the time. The first three are the Apostles’ Creed. The next 18 beads are the names for God in Hebrew.

“We conservative Protestants don’t do well with ritual. We can learn a lot from our Catholic brothers and sisters,” said Greenwood, an associate pastor at a Four Square Gospel church in north Edmonton.

“I discovered a God who had favour for me, and liked me. No matter what becomes of my beloved’s life in the future, God will be there for us and for that person.”

Today, although he is public about a large part of his own story, Greenwood keeps other details private, including his son’s condition or any other personal details.

Greenwood is one of five full-time and 10 casual chaplains at the Grey Nuns hospital. He works with mental health professionals, and shares his own story of recovery. However, he’s quick to add that when he works with patients, he keeps his story to himself so that it doesn’t affect his relationship with them.

Instead, Greenwood said his story informs his sense of compassion and clinical response to his clients.

Greenwood credits his faith, family, friends, co-workers and Covenant Health management for helping him in his recovery. Once a year he retreats to the bush of the Yukon or Alaska with only his fishing rods and his dog. And he continues a regular regiment of therapy, prayer and reading Scripture.

Given his own struggle with mental health, Greenwood’s advice is simple: “Make a call. Find a doctor. Find a psychiatrist. Step out of yourself.”

“It’s also the responsibility of the mentally ill to own their illness.”

Greenwood said he’s not usually afraid of public speaking, but telling this story wasn’t easy.

“Sharing my story is incredibly vulnerable. That was frightening. I feel relieved right now. This morning (before his speech) I felt like I’d rather be fishing.”