I met Father Stanley Rother, the first U.S.-born martyr to be proclaimed Blessed, over 40 years ago when I was just a teenager. I was born and raised in Oklahoma City. Our Archdiocese ran a mission in Guatemala along the shore of Lake Atilan, and I had gone along on a mission trip organized by a nun I knew.

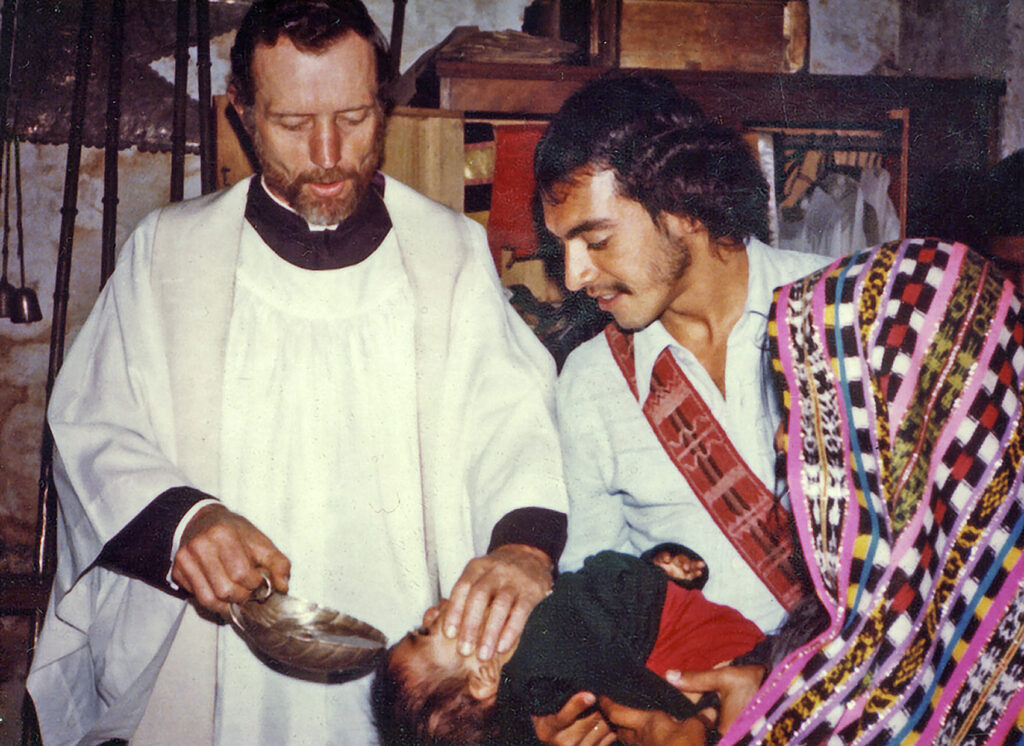

The Archdiocese of Oklahoma City announced that one its native sons, Father Stanley Rother, a North American priest who worked in Guatemala and was brutally murdered there in 1981, will be beatified Sept. 23 in Oklahoma. Father Rother is pictured in an undated file photo. (CNS photo/Charlene Scott)I had seen Father Stanley’s picture many times in the Sooner Catholic, our archdiocesan newspaper. The work he was doing in Guatemala among the Tz’utujil people, a Mayan culture, was well known across our state. We were justifiably very proud of him.

Oklahoma Catholics were a small minority, barely out of a time when we were the recipients of missionaries ourselves, so staffing a mission in a Third World locale was important to us. The mission in Guatemala was a godsend to a community that had rarely seen a travelling priest to partake of the sacraments.

My first in-person view of Father Rother was on a hot summer day at the end of a long bus ride. He was on top of a roof doing repairs. I thought he was one of the locals — until he climbed down the ladder and I could see his red beard, bobbing a head above the much shorter people.

That was his first lesson to us, that there is nothing wrong with performing simple labour. It was not his last lesson. He asked us how we had done in school, and what our plans for the future were. He told us his story of flunking out of seminary and thinking that his goal of becoming a priest was at an end.

Instead of it being the end, our bishop at the time sent him to a different seminary. This simple farm boy, who had opted to take agriculture in high school instead of Latin, would eventually learn not only Spanish, but also Tz’utujil. He wanted to learn Tz’utujil so that he could preach to his parishioners in their own tongue. He learned it so well that he translated the New Testament into Tz’utujil, a language that didn’t have a written form.

The two weeks I spent in Guatemala were transforming. I learned that even those with very little compared to our western standards could still live fulfilling, happy lives. I learned how important the sacraments could be to those who had done without. My family was far from wealthy, but compared to the people we met, we might have been millionaires.

I saw Father Rother interact with his parishioners. He was truly their shepherd. I wasn’t surprised to hear that he had gone back to Guatemala after hearing that his name was on a death list. A few years later, Archbishop Salatka told me he didn’t want to allow the priest to return to the mission, but was eventually talked into it.

Father Stanley Rother, a priest of the Oklahoma City Archdiocese, is pictured in an undated photo. He was brutally murdered in 1981 in the Guatemalan village where he ministered to the poor. Father Rother will be beatified Sept. 23 in Oklahoma. (CNS photo/Diane Clay, Sooner Catholic)Father Rother was adamant that he go back. He said plainly, a shepherd cannot run away. He wasn’t returning to die. He was returning to live. His life was in the highlands of Guatemala, far from the red dirt of Oklahoma.

His name had landed on the death list during the country’s civil war because he was taking care of his people, not for political reasons. He gave refuge to parishioners in danger. He searched for the bodies of the missing when their friends and family were too afraid. He wanted the tortured and murdered to have proper burials.

He had told everyone that if ‘they’ came for him, he would not allow them to take him. He didn’t want his body unfound. When masked men broke into the rectory, he screamed, “Kill me here!” He fought them with everything he had. They eventually shot him.

His parishioners sopped up every drop of his spilled blood, put it in jars, and placed them on the altar. People gathered from all around the lake as word spread that he had been killed. His body was returned to Oklahoma for burial, but his heart was buried where it had lived, in his church in Guatemala.

The day before we were to leave, Father Rother took us to meet a group of local ladies who were weaving clerical stoles. He was in the process of trying to establish a business for them to sell them stateside. He gave each of us girls a stole to take home to our pastors.

I admitted to him that I didn’t really like my pastor. He told me to save it for the priest who presides at my wedding. I carried it around longer than he, or I for that matter, could have imagined. But it finally found a home in Canada, with Father Patrick Baska, now pastor at south Edmonton’s St. Theresa Parish.

I had the opportunity to watch the beatification ceremony for Father Rother live-streamed from Oklahoma City on Sept. 23. As I watched, I was reminded of something else he told me. He said farming is a lot like being a priest. It’s hard work, and sometimes you don’t know what will grow from the seeds you plant. Some years the harvest is heavy, and some years it can be very lean. Either way, it requires the same amount of work.

I hope to live long enough to see his canonization. I have no doubt he is already among the saints.

Catherine Mardon is a writer, activist, retired lawyer and graduate of Newman Theological College in Edmonton.