The Archdiocese of Edmonton thanks Alberta Catholic school trustees and district staff for their leadership and sensitivity regarding the name of Bishop Vital-Justin Grandin, central Alberta’s first bishop.

Bishop Grandin represents a controversial and mixed legacy. While he is remembered for the many good things he accomplished, the association of his name with the tragic legacy of residential schools is a reminder to students, staff and the community of very painful experiences.

When the Truth and Reconciliation process held one of its national events in Edmonton in 2014, Archbishop Richard Smith offered a public apology on behalf of the Catholic Bishops of Alberta and the Northwest Territories for the harm done to students in residential schools by members of the Catholic Church.

However, healing will take a long, long time. For now, we can do our utmost to staunch the bleeding of the wound that’s been opened by recent events.

Archbishop Smith and the people of the Archdiocese share the anguish and sadness felt by Indigenous Peoples, and indeed all Canadians, after the discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves on former residential school sites in Saskatchewan and British Columbia.

The Archdiocese of Edmonton is committed to truth and to reconciliation. Archbishop Smith has pledged full transparency with respect to any relevant archives and records, and sharing them with the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, offering any support that we can to Indigenous peoples and continuing to walk together along the long road towards reconciliation led by Indigenous leaders themselves.

Here is additional information regarding residential schools in an FAQ we released recently.

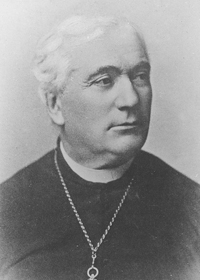

Background on Venerable Bishop Vital-Justin Grandin

Vital-Justin Grandin was born at St-Pierre-la-Cour, France, on February 8, 1829. In 1854, he was ordained a priest of the Oblate Missionaries of Mary Immaculate, a French order whose members were among the first missionaries to the country that would become Canada.

His first assignment was to the Métis settlement of St. Boniface in Manitoba, and just three years later at age 28, he was appointed coadjutor bishop, or assistant, to Bishop Alexandre Taché in the vast new Diocese of St. Boniface. The young priest had a speech impediment and suffered from chronic poor health, and records suggest he didn’t think he was worthy of the appointment. At his installation as Bishop of St Albert in 1871, he adopted the motto Infirma mundi elegit Deus (God chooses the weak of this world). Most Rev. Vital Grandin, OMI was the first Roman Catholic bishop of the Diocese of St. Albert, which would eventually be elevated to become the Catholic Archdiocese of Edmonton.

Bishop Grandin served nearly 50 years in what is now Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and the Northwest Territories. It’s estimated that he travelled more than 25,000 miles (just over 40,000 kilometres) on snowshoes and many more by dogsled and horseback as he visited remote missions across the region.

When he was appointed bishop of the St. Albert in 1871, Grandin had five Oblate priests to assist him. By the time he died in 1902, there were 52 priests and five congregations of religious sisters serving a diocese that had grown to 18,000 Catholics. Bishop Grandin had overseen the establishment of some 55 parishes and missions, more than 40 schools and orphanages, five hospitals, and the first seminary in Alberta.

Grandin battled with church officials over lack of funding for the Canadian missions, and eventually persuaded the Catholic Bishops to establish an annual collection. He advocated passionately for rights of Francophone Catholics to maintain their own language and schools.

He defended the land rights of the Métis and pleaded with government on behalf of starving Indigenous people. His fellow Oblate missionaries befriended the Blackfoot and Cree people, learned their languages, and assisted in negotiating several treaties across the prairies.

Missionaries often accompanied bison-hunting parties for months on their travels, sharing the joys and hardships of the hunters in order to share also the Gospel. Had it not been for the hospitality and skills of the First Nations people, many of the missionaries would have perished in the wilderness.

In an 1869 letter to the Oblate superior general in Rome, Grandin explained their approach to evangelization in the language of the day: “The best way, the only way to convert and to educate the infidels is to go live with them, to accompany them into their numerous camps for a part of the year.”

With the influx of white settlers and the demise of Prairie bison herds, Grandin became convinced that a European-style Catholic education was the only hope for the survival of the Indigenous people.

Bishop Grandin promoted the establishment of government-funded Indian residential schools, where Catholic priests and sisters would teach the skills needed to take up farming, trades, or household management. The Oblates would go on to operate nearly half the residential schools in Canada. It was a sentiment that was shared by officials in the government of Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald, which pursued an aggressive policy of assimilating Indigenous peoples.

The Catholic Church & the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Some accounts of Grandin’s role in the residential schools are included in the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The accounts are jarring to the contemporary reader.

The Oblates of Mary Immaculate have apologized formally for their role in the schools, first in 1991 and then again in 2014, at a TRC national event in Edmonton.

The Bishops of Alberta and the NWT also apologized at the same TRC event, and pledged to “continue to find ways for Catholics, together with other concerned Canadians, to support more effectively Aboriginal peoples in their ongoing struggles to achieve justice and equity in Canadian society.”

2021 Events

In a June 4 letter this year, Edmonton Archbishop Richard Smith reiterated his words from 2014 during the TRC listening circles:

“We apologize to those who experienced sexual and physical abuse in residential schools under Catholic administration. We also express our apology and regret for Catholic participation in government policies that resulted in children being separated from their families, and often suppressed Aboriginal culture and language at the residential schools.”

Archbishop Smith also committed the Archdiocese to “full transparency with respect to any relevant archives and records, and sharing them with the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation; offering any support that we can to Indigenous peoples, and continue walking together with them along the long road towards reconciliation.”

In a May 30, 2021 news release, Oblate Provincial Rev. Ken Thorson, expressed “heartfelt sadness and sincere regret for the deep pain and distress the discovery of the remains of children buried on the grounds of Kamloops Indian Residential School brings to the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation, and other affected Indigenous communities, especially family members of the deceased. I appreciate the sensitive and respectful way in which this difficult work is being carried out. This heart‐breaking discovery brings the tragedy of the residential school system into the light once again and demands that we continue to confront its legacy.”

The Oblates once again acknowledged in a June 24, 2021 news release, their sorrow for their involvement in residential schools and the harms they brought to Indigenous peoples and communities. They reiterated their commitment and intent to disclose all historical documents in their possession, in accordance with all legislation, about our involvement.

Mural at Grandin LRT Station

Francophonie Jeunesse de l’Alberta (FJA) board commissioned a mural in 1989 which depicts Bishop Grandin, and a nun holding an Indigenous baby. FJA said the mural was designed to honour Monseigneur Grandin for his contributions to Francophone culture, language, and religion. The 3-part mural also features images of St. Joachim Church, St. Joseph’s Cathedral Basilica, and Grandin Elementary School.

The mural at the Grandin / Gov’t Centre LRT station first sparked controversy in 2011 when there were calls for its removal. During this time, artists, academics, city officials, and other residents came together to come up with another solution.

Sylvie Nadeau, the original artist of the Grandin Mural, along with Cree and Métis artist Aaron Paquette worked together to create two additional works mounted on either side of the original — one showing a smiling Indigenous girl; the other showing a young boy as a strong youth.

In 2021, following news of the discovery of 215 unmarked graves at the former Kamloops Residential School, both Nadeau and Paquette (now an Edmonton city councillor) agreed it was time for the mural to come down.

Edmonton city council unanimously passed a motion on June 7, 2021 to cover up the Grandin LRT mural and to remove his name from the LRT station. The city will consult with a group of Indigenous and Francophone leaders. That group will work with the city’s naming committee to decide on a new name.

Reflection

In a reflection written after the TRC hearings, Father Forster (former Provincial of the Oblates) conceded that the good work done by Grandin and the Oblate missionaries will always be tempered.

“We, today, are very aware of the extremely negative impact of the residential schools on individual Aboriginal children and on the very fabric of society through destruction of family ties,” Forster wrote.

“At the disappearance of the buffalo and starvation that threatened the First Nations, the decision the Oblates made had an impact that reverberates to our day. They were men of their day, believing that assimilation was the only chance for survival as hunting was terminated.

“We might still ask the question today: What might have been the way to accompany First Nations to a new economy, after the demand for robes led to the extermination of the buffalo? Reservations, land grabbing, starvation, diseases were realities of the day. White man’s education as a co-operative of government and church, aimed at assimilation with aspirations of evangelization, was the path that was embraced by our Oblate pioneers.”

One of Bishop Grandin’s final acts was to ask for forgiveness as he lay on his deathbed in St. Albert in 1902. Bishop Émile Legal, would go on to succeed him as Archbishop of Edmonton.

In 1937, the Vatican issued a decree for the introduction of Grandin’s cause for beatification, a first step in the Church’s process of recognizing someone as a saint. Vital Justin Grandin was declared venerable in 1966, in recognition of his “heroic virtue”.

Historical Sources:

– Vital-Justin Grandin, Journal de Monseigneur Grandin, Missions 9 (1870):247

– Leon Doucet, The Journal and Memoir of Fr. Leon Doucet OMI 1868-1890: 37

– Library and Archives Canada, RG10, volume 3708, File 19502, part 1, Northwest Territories and Manitoba – Correspondence and Reports Regarding Roman Catholic Missions, Farms on Reserves, and Destitute Indians. Copy of a letter addressed to the Honourable Mr. Langevin, Minister of Public Works (original stamped 25 May 1880). Online MIKAN no. 2061654 (Original available online as pages 31–36, translations 37–43).

– Library and Archives Canada, RG10, volume 3708, File 19502, part 1, Northwest Territories and Manitoba – Correspondence and Reports Regarding Roman Catholic Missions, Farms on Reserves, and Destitute Indians, Grandin to Macdonald, September 27, 1880. Online MIKAN no. 2061654 (online pages 57-58).

– Frank J. Dolphin, Indian Bishop of the West, Vital Justin Grandin 1829-1902, Novalis 1986

Downloads

Printable versions of the two above documents may be downloaded as PDF files.