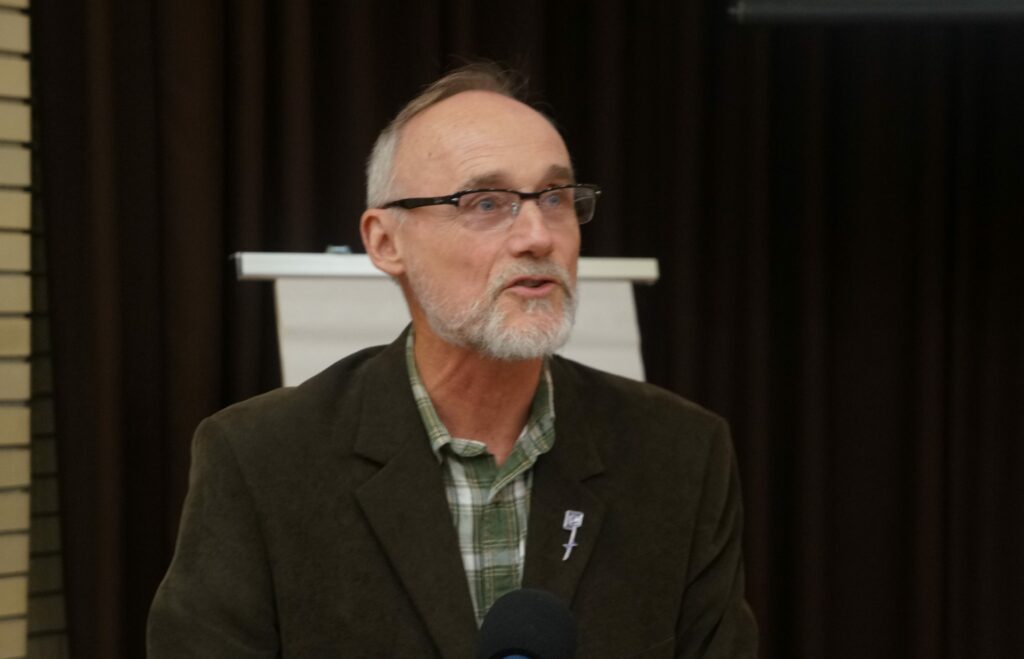

After ten years at the helm, Joe Gunn, is leaving Citizens for Public Justice to head up the new Oblate Centre at Saint Paul University in Ottawa.

The move on Feb. 11 brings full circle Gunn’s more than four-decade career in social justice work that began in the Catholic Church and ends with service for a program funded by the various Oblate of Mary Immaculate provinces in Canada, including Alberta.

“We will work on issues identified of concern to the Oblates: poverty in Canada; issues of environment; mining, especially Canadian mining in global south; and with the Oblates ongoing concern with aboriginal reconciliation,” said Gunn, 64, a former columnist with the Western Catholic Reporter.

“A huge thanks to CPJ after this decade with them. Thanks really to God and to everyone who has been so good to me.”

In his last weeks with CPJ, Gunn was on a book tour promoting Journeys to Justice: Reflections on Canadian Christian Activism, a series of interviews with some of the movers and shakers over the last several decades that Gunn conducted with CPJ’s blessing.

The project and his recent work helped him to take a long view of social change in Canada and the good Church leaders have accomplished — in everything from Canada’s health care system to her refugee sponsorship program.

“I think what CPJ offers is for people who know that deep changes take a long and dedicated time in coming, a way to stay faithful to best of Christian traditions and work together on these big Christian concerns,” he said.

Among the areas where he believes CPJ helped “move the ball forward” could be seen as relatively small successes. They tried to get the government to end travel loans for refugees, but instead were successful in getting it to drop the interest charges on the loans.

CPJ also worked with anti-poverty organizations on urging the government to adopt a national anti-poverty reduction plan. A bill calling for one is at second reading. “It’s an effort that took a decade of hard work,” he said. “We rarely see the massive breakthrough that people want to see, but we start with building hope and ways for people to move forward.”

CPJ’s Lenten campaign urging the government to be responsible on climate change started with a few congregations but has grown to include 100 in Catholic, Mennonite, Anglican and Christian Reformed churches, Gunn said. It is going into many Catholic schools as well.

“You’re perhaps touching people in ways you never know about,” he said. “That’s our hope, and to give people a sense of doing something a bit bigger.”

Gunn joined CPJ as executive director in 2008, taking over the Christian Reformed public policy think tank founded by Gerald Vandezande 55 years ago, after an 11- year stint as director of social affairs for the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops (CCCB).

“Most of the members were Christian Reformed people,” Gunn said. “There was some outreach. Some of the staff had other backgrounds.”

Gunn believes that when he joined it was time for CPJ to be “thinking more broadly.”

“For me, it was trying to find ways this organization that had been around for a long time, to find various structures of ecumenical movements to have some impact by getting lots of people involved,” he said.

Ten years later, the CPJ has a broader range of Christian religions, including two Catholic representatives, three people of colour, an aboriginal person and three representatives 30 or younger on its board and staff, he said.

Each members brings networks from their own faith tradition so CPJ’s work reaches out to wider networks, Gunn said. “I don’t think it’s referred to as an exclusively Calvinist organization anymore.”

The man replacing Gunn at CPJ is Willard Metzer, who worked at World Vision Canada and more recently as executive director of the Mennonite Church Canada.

“He’ll help CPJ grow and develop in some new ways.”

Gunn’s new role running The Oblate Centre, brings him back to his Catholic roots. Gunn grew up in a working class family in Scarborough, Ont. His father and uncles were all factory workers and he himself worked in a factory during summers and weekends. In the 1970s, he became involved in the Catholic Youth Movement, and joined the Youth Corps Movement of the Archdiocese of Toronto “that really engaged young people” in social justice work.

Part of that experience, involved going to Mexico during his last year of high school with some people from The Canadian Catholic Organization for Development and Peace to do an exchange program.

“We spent six weeks with people who worked with base Christian communities in Mexico City,” he said. “We saw how they worked with the poor and Indigenous people. We studied liberation theology, which was new to me as a high school student.”

In 1975, he was offered his first full time job at the animator of the social action office in the Archdiocese of Toronto. He spent three years “traveling around to frozen prairie landscapes,” acquainting himself with the Catholics involved in Development and Peace, which had no animators at the time. He learned about aboriginal issues and about the problems around uranium mining in the North.

The churches at that time had been helping Chilean refugees come to Canada after the 1973 coup.

When he arrived in Regina, and “hardly knew anyone,” he began “reaching out to Chilean refugee families” who had been “dropped in the freezing prairies.” He noted there were not programs for English-language training for refugees like there are now.

That familiarity with Mexico and Chilean refugees helped when Gunn was sent by the churches to be an observer on the borders of various Central American countries as war broke out.

“The churches decided we need to have vigilance on the border,” and Gunn first went on one of these trips. Then the non-governmental organizations (NGOs) decided there needed to be a more permanent presence in the region.

Gunn ended up spending seven years in Central America, visiting all the countries where there were refugees, sending back information, so programs could be developed to help refugees fleeing conflict in El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala.

He recalled visiting a camp in the jungles of Mexico that hadn’t been visited by the United Nations yet. He had three children he was trying to fly out to receive medical attention and one died in his arms. The pilot made him return the dead child to the parents on the runway.

“It was just horrible,” he said. But the experience taught him the people doing the best work in these camps were workers who came from the dioceses of the Catholic Church in Mexico. “These were the people doing the most incredible, selfless work.”

“What you found was faith in action,” he said. “The Church was a place where you could put your most cherished values and try to live them out in an organized way and in way that would have more impact.”

“It’s often when we try to do things on our own, our own feelings, our own human foibles get in the way,” he said. “We all need to find an organization, an institution that challenges us and helps us to be better.”

“My experience, despite her shadow history, there has always been ways through working in the Church to make me better and have a better impact on social change.”

After two years, he went to Nicaragua to work on a number of projects. It was in that country he met his wife-to-be, Suzanne, who was working for an American NGO.

After a total of seven years in Central America, the Gunns moved to Toronto where Joe took a position at the Jesuit Centre for Social Faith and Justice.

Gunn worked on Central American policy, and on the projects Jesuits were funding in Latin America for five years. The Gunns’ twin boys were born in Toronto.

In 1994, Gunn moved to Ottawa to become director of social affairs at the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops secretariat in Ottawa. “There was a pretty big outfit,” during many of his years at the CCCB, with two full-time directors, Gunn and one on the French side and a secretary for each.

The CCCB also had a director for Aboriginal affairs. But in 2004, the CCCB, in response to a large budget deficit, began to make cuts and restructure the Ottawa secretariat. Many positions were cut or hours and pay reduced. Gunn left one year after the cuts had substantially reduced both staff and budget.

“I left without a job,” he said. He picked up some freelance projects, but during his time at the CCCB he had developed many networks with ecumenical partners that led to his landing the position at CPJ.

“It takes a lot of energy and creativity and building relationships,” he said. “Sometimes we’re good at initiating things, but not as good at knowing when it’s time to move on, and bring in some new ideas.”

“I’m living in a little trepidation,” he admitted. “I’m hoping it will be a good piece of work with the Oblates going forward.”