Our History

A Century of Faith

A Journey of Faith Through Generations.

The Catholic Archdiocese of Edmonton traces its roots to the 19th century, when what is now Western Canada was a vast territory controlled by the powerful Hudson Bay Company. The inhabitants were mostly aboriginal peoples who made their livelihood through hunting, fishing and trapping. Fort Edmonton was the most important of the Hudson Bay Company’s trading posts, and its employees were generally French-speaking Catholics, many of whom transmitted the rudiments of their faith to their Métis children.

In 1822, Abbe Norbert Provencher, missionary of the Red River Settlement, became auxiliary to the Bishop of Quebec and was put in charge of this “District of the North,” an immense area spreading west from the Great Lakes to the Pacific coast and north to the Arctic Ocean.

In 1838, two priests on their way to the West Coast – Abbes Blanchet and Demers – stopped at Fort Edmonton, where they celebrated the first Mass, baptized children and blessed marriages. Their good report to Bishop Provencher led to the foundation of the first Roman Catholic mission at Lac Ste. Anne in 1843 and the building of the first chapel, a small log cabin within Fort Edmonton, in 1859.

Father Lacombe's log chapel at St. Albert, original seat of the diocese.

In 1861, Father Albert Lacombe, one of the earliest missionaries in the West, founded the St. Albert mission settlement and built a log chapel for ministering to the Cree and Métis. Father Lacombe Chapel, the oldest building in Alberta, is now a Provincial Heritage Site.

In 1871 the Diocese of St. Albert was created. Several factors necessitated this move: the confederation of provinces in Canada with the promise of a transcontinental railway; the rapid disappearance of the buffalo with the resulting starvation of First Nations and Métis people, the heavy influx of white settlers of different ethnic origins and faiths, the problem of land and schools for First Nations people, the shortage of missionaries, schools and churches for the newcomers.

By 1889 the Saskatchewan portion was separated from the huge diocese. In the subsequent years the herds of buffalo totally disappeared, and the First Nations who signed treaties were given tracts of land and became wards of the government. Women and men religious congregations arrived to open schools for aboriginal and settler children, hospitals and asylums for the elderly. They visited families scattered over the land, encouraging newcomers to group in parishes. It is estimated that St. Albert’s first bishop, Bishop Vital Grandin, walked 25,000 miles by snowshoe as he ministered to the huge diocese. When he died in 1902, the diocese had a population of some 18,000 Catholics in 30 organized parishes served by 42 Oblate Fathers and 10 secular priests.

On Nov. 30, 1912, the Episcopal See of St. Albert was raised to the status of Archdiocese of Edmonton, and its southern portion removed to form the Diocese of Calgary. Archbishop Emile Legal became the first Archbishop of Edmonton. When he died in 1920, the Catholic population of the Archdiocese numbered 38,400; there were 92 religious priests and 28 diocesan priests serving in 55 parishes and 58 missions with churches.

St. Albert Church under construction, early 20th century.

The Archdiocese continued to grow rapidly after the end of the First World War. The basement of St. Joseph Cathedral was built (1925); a diocesan Catholic newspaper was published (1921); St. Joseph College was incorporated (1926); the diocesan seminary opened its doors (1927). Once again, a portion of the Archdiocese was carved out; this time, it was the northern section that became the Diocese of St. Paul in 1948.

Today the Archdiocese of Edmonton includes the greater Edmonton area but also covers a geographic region stretching from the Rocky Mountains in the west to the Saskatchewan boundary in the east, from Didsbury in the south to Mayerthorpe in the north. In total the Archdiocese covers 150,000 square kilometres. It includes 61 parishes with resident priests in cities, towns, rural areas and native communities, and another 64 parishes and missions without resident priests. Within its boundaries are nine Catholic school districts and 10 Catholic health facilities including hospitals, continuing care centres and seniors residences.

Every Sunday, Mass is celebrated in many different languages, including French, Spanish, Polish, Chinese, Croatian, Portuguese, Vietnamese, Italian, German, Hungarian, Korean, Latin and American Sign Language.

Every July, thousands of First Nations Catholics gather on the shores of Lac Ste. Anne for an annual pilgrimage that began more than a hundred years ago. The pilgrimage, a time of reunion, renewal and healing attended by Pope Francis in 2022, has become one of the largest annual gatherings of First Nations people in Canada. And each August, another focal point for the faithful is the pilgrimage to Skaro, where Polish settlers in 1919 built a replica of the grotto at the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Lourdes in France.

Coat of Arms

A Journey of Faith Through Generations.

Context

The Pope and most bishops adopt a personal coat of arms, which today is used primarily to identify communications from their particular office.

A coat of arms is also commonly used to identify a diocese or Archdiocese.

The armorial bearings of the Catholic Archdiocese of Edmonton were granted by the Chief Herald of Canada on 20 November 2009.

Heraldic Description of Arms

(In Blazon, the language of heraldry)

Azure a chevron Argent between in chief, two ears of wheat in saltire, and two snowshoes in saltire, and in base a Chi-Rho Or.

Background

Heraldry originated about a thousand years ago in Europe, where it was used by the warrior classes as a means of differentiating combatants on the field of battle. As Europe developed and the feudal warrior class disappeared, the practice of identifying one's possessions with personal emblems flourished.

Ecclesiastical heraldry grew out of this practice, initially to differentiate between the various degrees of the clerical estate.

The Symbolism

For our new coat of arms, we turned to the Canadian Heraldic Authority, which is commissioned to carry out this work by the Governor General.

- The mitre used was created especially for Canadian Catholic dioceses.

- On the gold orpheys are three blue crosses with lily-like terminations; the number three indicates the Holy Trinity and the lily is a symbol of St. Joseph, patron of the Church in Canada.

- On the lappets (white with gold lining) are red crosses with maple leaf terminations, representative of Canada. The crosses have a double transverse, indicating the metropolitan cross of an archdiocese.

- On the shield, the colour blue refers to the healing waters of Lac Ste. Anne, the site of the first Catholic mission in the area, to the waters of Baptism, and to Mary, the mother of Christ.

- White refers to the truth and hope Christians find in the Gospel, while gold refers to the providence and glory of God.

- The chevron represents a carpenter’s square, another emblem of St. Joseph, the patron of the Archdiocese. It also alludes to the Rocky Mountains in the west of the Archdiocese.

- The ears of wheat are a Eucharistic symbol of the Bread of Life; they also refer to prairie agriculture.

- The snowshoes represent the ministry of the first bishop, Vital Grandin, who was said to have walked 25,000 miles in snowshoes during his ministry.

- The Chi-Rho, which combines the Greek letters X and P (Ch and R in the Roman alphabet), refers to the name of Christ.

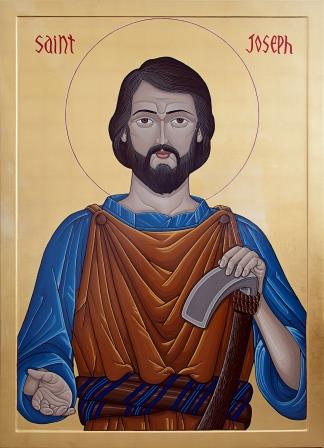

Icon of St. Joseph the Worker

In honour of the 100th anniversary of the Archdiocese, iconographer Andre Prevost was commissioned to write a new icon of our patron saint. Here are some reflections on this prayerful work, in the iconographer's words:

Artist's Commentary

It has been a great blessing to write the icon of St. Joseph the Worker. Most icons to date which bear the name of St. Joseph the Worker are traditional portrayals of St. Joseph with the Christ Child, wearing the himation (outer garment) and usually holding the flowering staff or holding a set square (as a representation of his carpentry).

St. Joseph is portrayed in his middle years, in this new icon, wearing a pale blue tunic with rolled up sleeves and a leather earth-toned shop apron, which is buttoned at the shoulder. He is presented in 'working' clothes and not wearing the traditional himation, which would not be worn while working. The tradition of use of blue (or purple) for the inner garment represents the spiritual, and the outer garment is in warm brown colours for the earth. The blue in the detailing on his waist sash represents that St. Joseph was from the lineage of the House of David. His left hand rests on a wood-chipping tool and reaches out with his right, inviting people to himself.

Referenced to the Byzantine Tradition, the design is such for a stronger focus on St. Joseph’s title.

It was important to His Grace Archbishop Richard Smith that the icon be a reminder to us to be open to the working of God in our lives, and an invitation to us to trust in what God is doing, as Joseph did.

“It also would be consonant with the traditional admonition of the Church ‘Ite ad Joseph’ (Go to Joseph) to seek the intercession of the patron saint of the universal Church.”

An icon is referred to as having being 'written' and not 'painted.' This is because it is not associated to the fine arts: it isn’t about artistic creation but about tradition, unchanging guidelines and the iconographic theology that sees an icon as sacramental and in the same light as the written Word. An icon is not just an image to be looked upon, but connects with the viewer and draws he/she into itself and directly to its prototype (in this case, St. Joseph) and through it, to God’s saving grace.

The process for each icon is a journey for the iconographer; certainly one of patience as an icon will take the time that it requires. Every step is deeply set within tradition and rich in symbolism, guiding the spiritual journey. It begins with the wood panel, the symbol of the Tree of Knowledge (Garden of Eden) and the Tree of Life (the Cross). This icon is constructed in solid poplar and has two parts: the outer part ‘container’ (the raised frame area) and the inner part ‘the contained’ (the inset area); also symbolizing the two natures of the human being – the body and the soul. (You will note that it also has extra braces along the back of the icon to help prevent the natural warping of wood over time.)

The board is covered with linen cloth, which symbolizes the ‘Shroud’, dying to ourselves to enter the Kingdom. Aside from the practical preparation of the panel to receive paint, the white gesso symbolizes light creating a new room for beauty.

After the image is transferred on the panel, the Bole (a red clay base) is then applied to the sides and also to the front surfaces where the gold leafing will be adhered to - representing our nature in God’s Creation. It symbolizes the ‘old humanity’; the clay in the inner surface (under the gilding) symbolizes the ‘new humanity’.

The 24K gold background is the prime symbol. Gold symbolizes Heaven. Gold applied on clay (bole) symbolizes Heaven’s plans for Humanity, representing the union of Heaven and Earth. I only use an archival quality acrylic paint which is higher in pigment content, does not fade over time, and for its longevity. The key is that it is water based. Oil paint cannot be used for icons as water symbolizes the rituals of purification, the waters of Baptism. Colours are a gift of God, such as when God presented Noah with the colours of the rainbow. As we add more and more colours and highlights, paint moves us from original chaos to shape and order. That is why I never use black paint in an icon. It may appear as though black is used for details, but it is fact dark greens, dark red purple, and a dark blue (Anthraquinone Blue). The colour black is the absence of God’s light.

When an icon reaches completion, the white circle is often drawn around the original red halo as a sign, not that perfection has been achieved, but that this particular transfiguration has been completed; it also symbolizes the iconographer’s return to the white panel; the determination to start all over again with a new board (a new white gessoed panel).

The oil varnish at the end symbolizes anointing, the consecration of a chosen one. An iconographer learns quickly that if any step is rushed or simplified, it inevitably results in failure in later stages. With every icon, the icon guides the journey. The iconographer becomes a participant.

![]()

Andre J. Prevost

2013

Past Bishops

Most Rev. Richard W. Smith, M.Div., S.T.L., S.T.D., D.D.

Archbishop of Vancouver

2025-Present

Archbishop of Edmonton

March 22, 2007 – February 25, 2025

Most Rev. Gregory J. Bittman, B.Sc.N., M.Div., J.C.L.

Bishop of Nelson

2018-Present

Auxiliary Bishop of Edmonton

July 14, 2012 – February 6, 2018

Thomas Cardinal Collins, M.A., S.S.L., S.T.D., D.D.,

Archbishop of Toronto

2006 – present

Archbishop of Edmonton

June 7, 1999 – December 16, 2006

Most Rev. Joseph MacNeil, J.C.D., D.D.

Archbishop Emeritus

1999-2018

Archbishop of Edmonton

July 2, 1973 – June 7, 1999

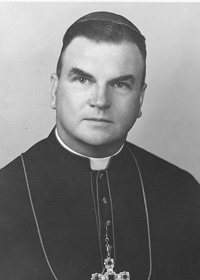

Most Rev. Anthony Jordan, OMI, D.D.

Archbishop of Edmonton

August 11, 1964 – July 2, 1973

Coadjutor Archbishop of Edmonton

1955-1964

Most Rev. John Hugh MacDonald

Archbishop of Edmonton

March 5, 1938 – August 11, 1964

Coadjutor Archbishop of Edmonton

1936-1938

Most Rev. Henry Joseph O’Leary, D.D.

Archbishop of Edmonton

September 7, 1920 – March 5, 1938

Most Rev. Emile Legal, OMI D.D.

Archbishop of Edmonton

November 30, 1912 – March 10, 1920

Bishop of St. Albert

1902-1912

Coadjutor Bishop of St. Albert

1897-1902

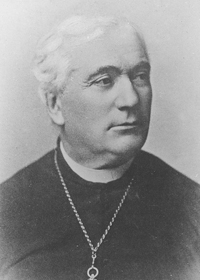

Most Rev. Vital Grandin, OMI D.D.

Bishop of St. Albert

September 22, 1871 – June 3, 1902